If you want to get anything done, there are two basic ways to get yourself to do it.

The first, more popular and devastatingly wrong option is to try to motivate yourself.

The second, somewhat unpopular and entirely correct choice is to cultivate discipline.

This is one of these situations where adopting a different perspective immediately results in superior outcomes. Few uses of the term “paradigm shift” are actually legitimate, but this one is. It’s a lightbulb moment.

What’s the difference?

Motivation, broadly speaking, operates on the erroneous assumption that a particular mental or emotional state is necessary to complete a task.

That’s completely the wrong way around.

Discipline, by contrast, separates outwards functioning from moods and feelings and thereby ironically circumvents the problem by consistently improving them.

The implications are huge.

Successful completion of tasks brings about the inner states that chronic procrastinators think they need to initiate tasks in the first place.

Put in simpler form, you don’t wait until you’re in olympic form to start training. You train to get into olympic form.

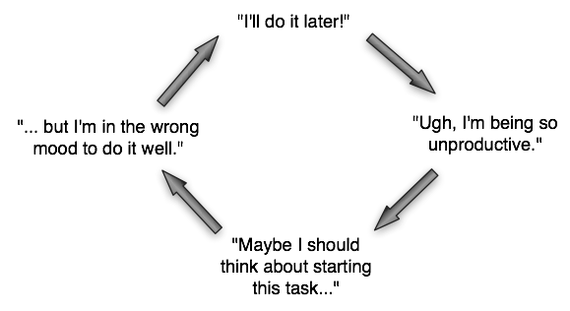

If action is conditional on feelings, waiting for the right mood becomes a particularly insidious form of procrastination. I know that too well, and wish somebody pointed it out for me twenty, fifteen or ten years ago before I learned the difference the hard way.

If you wait until you feel like doing stuff, you’re fucked. That’s precisely how the dreaded procrastinatory loops come about.

At its core, chasing motivation is insistence on the infantile fantasy that we should only be doing things we feel like doing. The problem is then framed thus: “How do I get myself to feel like doing what I have rationally decided to do?”. Bad.

The proper question is “How do I make my feelings inconsequential and do the things I consciously want to do without being a little bitch about it?”.

The point is to cut the link between feelings and actions, and do it anyway. You get to feel good and buzzed and energetic and eager afterwards.

Motivation has this the wrong way around. I am utterly 100% convinced that this faulty frame is the main driver of the “sitting about in underwear playing Xbox, and with yourself” epidemic currently sweeping developed countries.

There are psychological problems with relying on motivation as well.

Because real life in the real world occasionally requires people do things that nobody in their right mind can be massively enthusiastic about, “motivation” runs into the insurmountable obstacle of trying to elicit enthusiasm for things that objectively do not merit it. The only solution besides slackery, then, is to put people out of their right minds. That’s a horrible, and fortunately fallacious, dilemma.

Trying to drum up enthusiasm for fundamentally dull and soul crushing activities is literally a form of deliberate psychological self-harm, a voluntary insanity: “I AM SO PASSIONATE ABOUT THESE SPREADSHEETS, I CAN’T WAIT TO FILL OUT THE EQUATION FOR FUTURE VALUE OF ANNUITY, I LOVE MY JOB SOOO MUCH!”

I do not consider self-inflicted episodes of hypomania the optimal driver of human activity. A thymic compensation via depressive episodes is inevitable, since the human brain will not tolerate abuse indefinitely. There are stops and safety valves. There are hormonal hangovers.

The worst thing that can happen is succeeding at the wrong thing – temporarily. A far superior scenario is retaining sanity, which unfortunately tends to be misinterpreted as moral failure: “I still don’t love my pointless paper-shuffling job, I must be doing something wrong.” “I still prefer cake to brocolli and can’t lose weight, maybe I’m just weak”. “I should buy another book about motivation”. Bullshit. The critical error is even approaching those issues in terms of motivation or lack thereof. The answer is discipline, not motivation.

There is another, practical problem with motivation. It has a tiny shelf life, and needs constant refreshing.

Motivation is like manually winding up a crank to deliver a burst of force. At best, it stores and converts energy to a particular purpose. There are situations where it is the correct attitude, one-offs where getting psyched and spring-loading a metric fuckton of mental energy upfront is the best course of action. Olympic races and prison breaks come to mind. But it is a horrible basis for regular day-to-day functioning, and anything like consistent long-term results.

By contrast, discipline is like an engine that, once kickstarted, actually supplies energy to the system.

Productivity has no requisite mental states. For consistent, long-term results, discipline trumps motivation, runs circles around it, bangs its mom and eats its lunch.

In summary, motivation is trying to feel like doing stuff. Discipline is doing it even if you don’t feel like it.

You get to feel good afterwards.

Discipline, in short, is a system, whereas motivation is analogous to goals. There is a symmetry. Discipline is more or less self-perpetuating and constant, whereas motivation is a bursty kind of thing.

How do you cultivate discipline? By building habits – starting as small as you can manage, even microscopic, and gathering momentum, reinvesting it in progressively bigger changes to your routine, and building a positive feedback loop.

Motivation is a counterproductive attitude to productivity. What counts is discipline.

Update: there’s part 2.

Enjoying the reading? Consider supporting Wisdomination.com on Patreon.